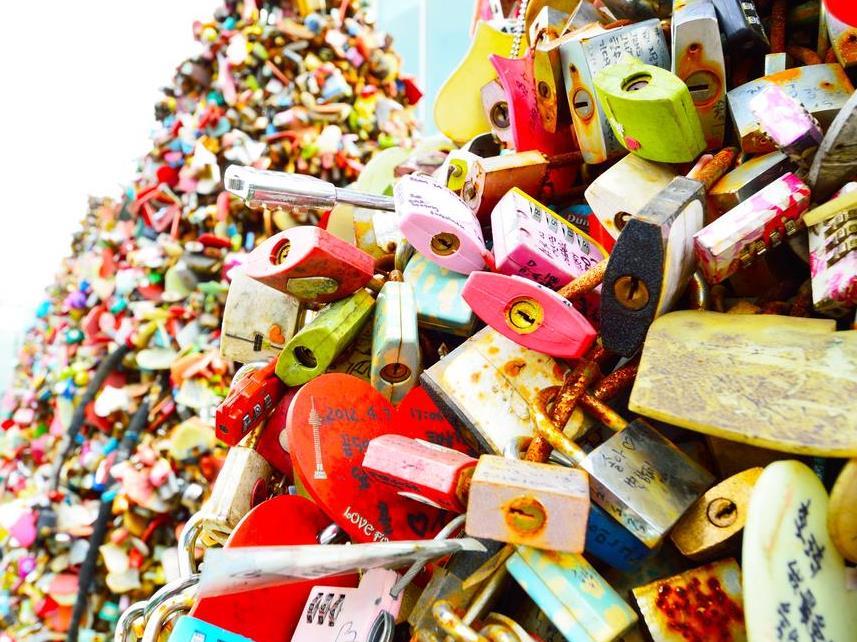

Brand loyalty is the key. Credit: Tanjala Gica / Shutterstock.com.

Brand designers are battling it out to compete in a world where consumers are more savvy, less loyal and swamped by choice. In an American study by Ernst & Young only 25% of consumers said that brand loyalty affected their choices when they shopped.

Before the Internet, consumers used to rely on a brand’s reputation to determine what type of quality they would be afforded post-purchase. “Beans means Heinz.” “Ah McCain, you’ve done it again.” Now, with a wealth of information at their fingertips, consumers are forgoing reputation in favour of information.

Take the car industry for example. Long-trusted brands like Ford, Holden and Toyota are falling by the wayside. Their brand alone – and they each had good standing within the wider community – couldn’t help them when it came to a failure in demand for the product versus its cost to make.

Michael Ramah in in his Huffington Post article Brand with Benefits writes, ‘No matter how tempting it may seem, today’s brands should ease up on their singular goal of a long-term, monogamous relationship with consumers. No matter how much they like it, they ain’t gonna put a ring on it. Instead, brand managers will find greater degrees of engagement if they start a little more casually and demand a little less commitment up front. More “friends with benefits” than “til death do you part”.

It seems, as Ramah writes, that there is room for consumers to have more than a few partners and feedback on that partner is becoming increasingly popular, with sites like Yelp, Urbanspoon, Product Review and Trip Advisor can all make an impact on how a business is perceived. Branding is no longer a one way street.

This is where intelligent branding and design need to step in with creative strategies for success.

Designers need to one-up their consumers and think savvy and laterally about not just their marketing, but also their product and perception. It is the age of the start-up and the crowdfunding campaign, which both make way for smaller, smarter products to edge in as the monoliths topple. Here, the distance between product and end user has shrunk.

With the recent announcement that Qantas will be cutting five thousand jobs, it is pretty clear that consumers aren’t even loyal to brands that carry national significance and historical connection. People are more than happy to go to elsewhere if they are offered better service and cheaper flights. Loyalty points schemes have done little to address the issue.

In the New Yorker, James Surowiecki writes, ‘It’s a truism of business-book thinking that a company’s brand is its “most important asset,” more valuable than technology or patents or manufacturing prowess. But brands have never been more fragile.’

On the flipside of this Karl Treacher, a behaviour analyst and organisational ecologist, writes in Marketing Magazine that, ‘Consumers today are more brand loyal than ever, and expect to see under the hood’ in order to best understand a brand’s value and how it aligns with their values, lifestyle and ambitions.’

Brands need to be more open, both in how their products are made and their response to feedback. Having a back story, being honest with consumers and providing a product responsive to their needs can keep people coming back. Failing to do so will see customers drop off significantly. Humans are hard-wired to attach a narrative to their surroundings. They are therefore more than willing to cast your brand as the villain if given the opportunity.

Surowiecki points to the example of Canadian yoga company Lululemon Athletica, which developed a cult-like following for their yoga clothing some years back. But they suffered a branding crisis when the narrative surrounding the product collapsed.

It began when consumers complained about poor quality clothing, which meant pants so thin they became see-through when running through a bendy yoga routine. The founder – who has since stepped down – responded by observing caustically that perhaps some ladies were too fat to wear the clothes. In addition despite their high cost, the clothes were also found to still be made in Bangladesh, which isn’t exactly renowned for its strong worker’s rights reputation. A villain was cast, and sales have been decelerating since.

While this might seem like a fickle environment for a business to survive in, for those who are willing to design the product and create the mentality that consumers are looking for, there are more opportunities than ever to thrive.